Sidy Cissoko on New NBA Contract: 'I'm Not Going to Change'

Cissoko signed a new two-year deal last week.

In the first of a two-part series, a look at how local and national media outlets covered the divorce of Walton and the Trail Blazers.

This story was originally published last summer. Following Monday’s news of Bill Walton’s passing at the age of 71, I’m removing the paywall and re-sharing it. I may write something on Walton at some point if I feel I have anything new to say that isn’t covered in any of the countless tributes that have started to come out today, but those of you who didn’t see this story last July may find it interesting.

Damian Lillard's July 1 trade request has shaken up the Trail Blazers' offseason, and how the exit of the franchise's all-time leading scorer is resolved will define how the next half-decade or more of basketball in Portland unfolds.

This is not the first time the face of the Blazers has asked to be traded. It happened twice before, with both of the other players in contention for the title of "best Blazer ever": Bill Walton in 1978 and Clyde Drexler in 1995.

Since both of the Blazers' previous superstar divorces were before my time (Walton's came 11 years before I was born, Drexler's when I was in kindergarten), I was curious about how they were covered in the media at the time.

It goes without saying that today's media environment is not the same as the one that existed in the 1970s or the 1990s. Social media has replaced newspapers as the most dominant source of information, and with that comes simply a higher volume of content on any topic and a lot more garbage to sort through.

The public attitude towards this kind of stuff has also flipped in the years since The Decision in 2010. It was far more common before then for the public, and newspaper columnists, to turn on players and call them selfish or entitled when they asked to be traded. Today, in the "player empowerment" era, it's mostly celebrated.

But in researching old newspaper and magazine articles from the late '70s and mid '90s, I was struck by how similar the framing and coverage of the Walton and Drexler situations were to how Lillard's trade request is talked about now, just in a different medium. It's a fascinating reminder that pro sports have always been largely the same through the decades.

This will be a two-part series. Today, we're going to look at the coverage of Walton's departure from Portland, from the time he requested a trade on Aug. 5, 1978 through his holdout during the 1978-79 season to when he ultimately left in free agency that summer to sign with the San Diego Clippers.

The necessary background that likely everyone knows: Coming off their first and only championship in franchise history, the Blazers started the 1977-78 season 50-10 before Walton suffered a broken foot in February. Despite his season being cut short, he was dominant enough to be voted MVP of the league. Walton returned for the first two games of Portland's playoff series against Seattle, but re-aggravated the foot injury and was sidelined again as the Blazers lost to the Sonics in six games.

That summer, Walton requested a trade out of Portland and accused the Blazers' medical staff of mismanaging his health and forcing him to take painkillers to be available to play. The standoff dragged out into the summer and through the entire following season before Walton finally joined the Clippers as a free agent. Reading contemporary coverage, there are eerie similarities between the way it was covered and the way Lillard's situation is being covered now.

In the pre-internet days, the rumors and misinformation that today run wild on questionable Twitter accounts with paid-for blue checks often made it into print.

A story published on Aug. 4, 1978 in the now-defunct Oregon Journal cited a report from a Portland radio station that claimed Walton had already been traded to San Diego, which had been picked up on local television newscasts in San Francisco and Washington. Then-New York Times NBA writer Sam Goldaper told the paper that a freelance writer from Portland who was covering a Yankees-Red Sox game in New York had been telling people that the Blazers would be holding a press conference the following day to announce the trade. The team confirmed to the paper that a press release was scheduled for the next day but did not say what it would be.

The following day, the Blazers issued a press release that read, in full: "The Portland Trail Blazers announced today that Bill Walton has asked to be traded prior to the 1978-79 season and the club has informed him that it will attempt to abide by his request."

Walton issued his own statement through his representatives, Jack Scott and John Bassett, that read in part: "This was the most difficult decision I've ever had to make regarding my basketball career. The tremendous loyalty and support of my teammates and the Trail Blazer fans have made that decision much tougher."

Walton, whose contract gave him veto power over trades, reportedly gave the Blazers a list of seven teams he'd be open to playing for: the Lakers, Knicks, Celtics, Clippers, Nuggets, Sixers and Warriors.

Scott was a relatively recent addition to Walton's inner circle, and that same year wrote a book called Bill Walton: On the Road With the Portland Trail Blazers. For most of the summer, he served as Walton's public mouthpiece, much to the dismay of both the Blazers and others close to Walton. In an Aug. 9 story for The Oregonian, columnist Leo Davis wrote that most fans viewed Scott as the driving force behind the trade request, and didn’t believe it was coming from Walton himself.

It was reported that Walton and the Blazers had agreed that neither of them would comment publicly on the reasons behind the trade request—not that that stopped details from getting out about Walton's frustrations with the team's medical staff. Scott wasted no time in giving interviews alluding to the issues Walton had with the organization.

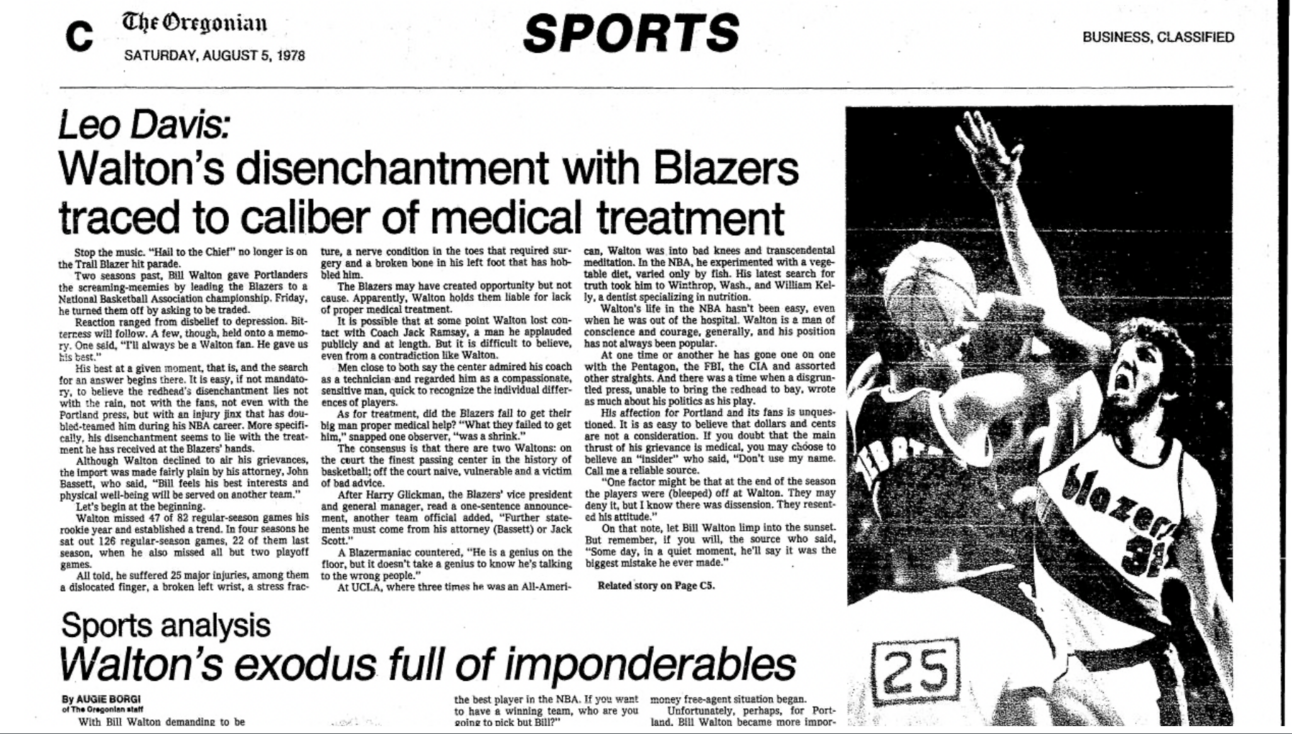

The Oregonian (August 5, 1978)

Both the Oregonian and Oregon Journal had wall-to-wall coverage, as you'd expect. In addition to the news story, both papers came with reporting about the cause of Walton's unhappiness (the medical staff's treatment of his injuries), reaction from the organization and a look at his trade market, which was not very strong, both because most of the teams on his list already had a starting center, and because teams were wary of his injury history.

The Blazers maintained that, despite Walton having a no-trade clause, they were looking for a significant return. Walton's representatives did not see it that way, with Bassett telling the Journal: "With the scenario being what it is, it's much less likely Portland will get what it would have had the circumstances been different."

Scott, Walton's other representative, doubled down to the Journal's Blazers beat reporter, Ken Wheeler: "Bill's position is that he questions if there should be any compensation at all. He feels very strongly that he is not going to allow the team that he goes to to be damaged by his acquisition. He's leaving because he feels mistakes were made by Portland. He does not believe he or the team which acquires him should pay for Portland's mistakes."

The Monday after Walton's trade request, the Blazers offered season-ticket holders the option of a refund, and reportedly only five people took them up on it. Meanwhile, a group called "Kids for Walton" launched a petition with the goal of getting 100,000 signatures to convince Walton to rescind his trade request. That same week, representatives from teams began coming to Portland to meet with Walton. The Knicks were believed to be the frontrunners, with multiple days of meetings involving head coach Willis Reed and several MSG executives.

Nowadays, team personnel are explicitly prohibited from commenting publicly on players on other teams, or about ongoing trade negotiations, which is why every trade rumor you hear is laundered through “league sources.” This wasn’t always the case. It wasn’t uncommon in decades past for front-office executives to comment on the record about potential trade packages. A potential Walton trade with the Knicks for Marvin Webster, for example, is something today that you’d hear about discussed in vague terms on podcast, often with some kind of disclaimer not to aggregate it because it’s not reporting. In 1978, everything was right there in the paper, with the GM’s name on it.

The Oregonian (August 9, 1978)

A Journal story from the day of the trade request rounded up fan reaction that's indistinguishable from tweets you see in these sorts of situations now. One person wondered whether the trade request was actually coming from Walton or if he was being influenced by people close to him. A fan named John Marino hoped Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wasn't the return in the trade because he wouldn't fit in Jack Ramsay's offense, which is peak 2009-era Blazersedge energy 30 years ahead of its time.

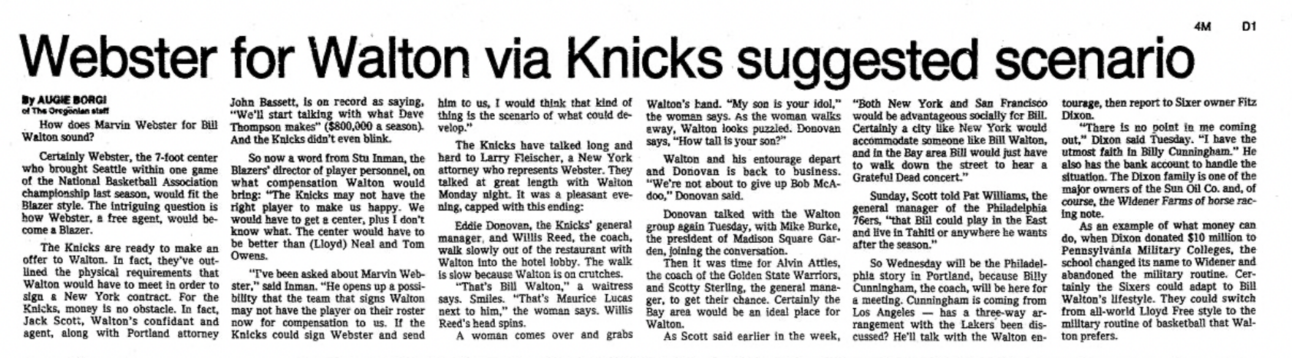

Needless to say, the reigning league MVP requesting a trade out of Portland one year removed from leading the Blazers to a championship was a massive story nationally as well as locally. It made the Aug. 21 cover of Sports Illustrated with a story written by John Papanek called "Off on a Wronged Foot."

Sports Illustrated (August 21, 1978)

The SI story detailed a secret meeting Walton had with Blazers brass in Chicago on Aug. 1 in which he asked to be traded, several days before the trade request went public. It also ran through concerns Walton and other players had about the Blazers' medical staff, including allegations that the team overprescribed painkillers.

On Aug. 14, Walton and his representatives decided the Warriors were the team he wanted to join, with Scott telling The Oregonian: "We felt it was the one area of the country that he'd get the same support from fans that he got here."

The Blazers began trade negotiations with the Warriors, which didn't get very far. Walton's representatives, Scott and Bassett, threatened a medical malpractice lawsuit against the team if a trade agreement wasn't reached swiftly, while the Blazers insisted they were in no rush and wouldn't make a bad deal.

The Oregonian (August 22, 1978)

"Bill Walton's advisors announced his choice of Golden State Sunday night," team president Harry Glickman told the Journal on Aug. 22. "On Monday morning and each day since, we have notified Golden State that [director of player personnel] Stu Inman and I were ready to sit down and attempt to negotiate in good faith. … When, and if, we do sit down to negotiate, the decision on whether we make a trade will be based on what will be best for the Portland Trail Blazers, not on any threat of a lawsuit."

Journal columnist George Pasero argued the same week that it was in the Blazers' best interests to just take whatever they could get for Walton and wash their hands of the situation.

"Can't blame the Blazers for wanting a value return, although it's unrealistic to believe Portland will obtain anyone of the quality of Walton," Pasero wrote. "From the Blazer standpoint, it has to be 'Get on with it.'"

Just as they do on Twitter now, national NBA reporters dropped little tidbits in their newspapers about the talks. One rumor had the New Jersey Nets offering Walton a plot of land in addition to his salary to come play for them. There was talk that the Knicks’ reported interest was nothing more than a leverage play by the Blazers' to increase the asking price with the Warriors. All of this came from anonymous sources. TheNBACentral would have thrived in the ‘70s.

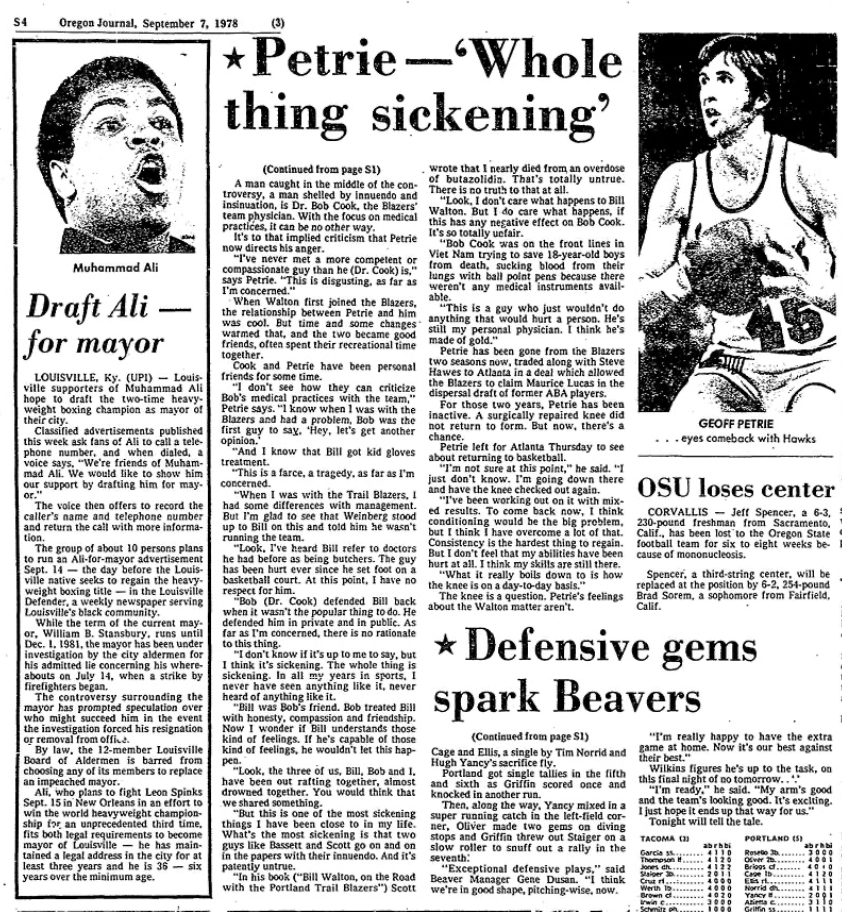

On Sept. 7, former Blazers guard Geoff Petrie, the franchise's first-ever draft pick, ripped Scott and Bassett in an interview with the Journal, calling them "social misfits" who had been manipulating Walton. Petrie called the situation a "tragedy" and a "farce," and said he had "no respect" for Walton.

Oregon Journal (September 7, 1978)

That same day, Walton met with Blazers owner Larry Weinberg in an attempt to reconcile. Those talks went nowhere, and the team issued a statement that read: "The Trail Blazers and Walton will continue to seek a trade satisfactory to both."

It was understood that Walton would likely be away from the team until they worked out a trade. While Golden State was understood to be his preferred choice, the Clippers also announced they were getting into the bidding.

Up until this point, Walton himself had said nothing. On Sept. 9, 1978, right before the start of training camp, he gave an interview to the local radio station KINK-FM, which he said would "probably be the last time I speak here in Oregon."

In the interview, Walton laid out all of the reasons he was asking for a trade. He confirmed that the Blazers' medical staff's policies were the driving force, saying that he was ridiculed by teammates for not being willing to take painkillers, and also that he had asked Weinberg to change some policies and fire certain members of the medical staff, to no avail. Walton also called out the "cavalier attitude" of the local media.

Blazers training camp began at Mount Hood Community College, with the big story being the addition of No. 1 overall pick Mychal Thompson.

"When I first heard [Walton] wouldn't play, I knew we wouldn't have as good a shot at the championship," Thompson told The Oregonian. "I also knew I'd get much more playing time. I'm not worrying about it. Whatever happened between Bill and the team has nothing to do with me."

An editorial in the Oregon Journal called Walton selfish for saying, “I was 50-10” at the time of his injury.

Walton was largely out-of-sight-out-of-mind for the Blazers once the 1978-79 season began, but the subject still came up occasionally. On Oct. 14, 1978, Sporting News columnist Bill Livingston wrote about the NBA's "Summer of Discontent," tying in other stars like Rick Barry, Tiny Archibald and Bobby Jones also changing teams. That's more or less every offseason and trade deadline in the NBA in 2023.

The Sporting News (October 14, 1978)

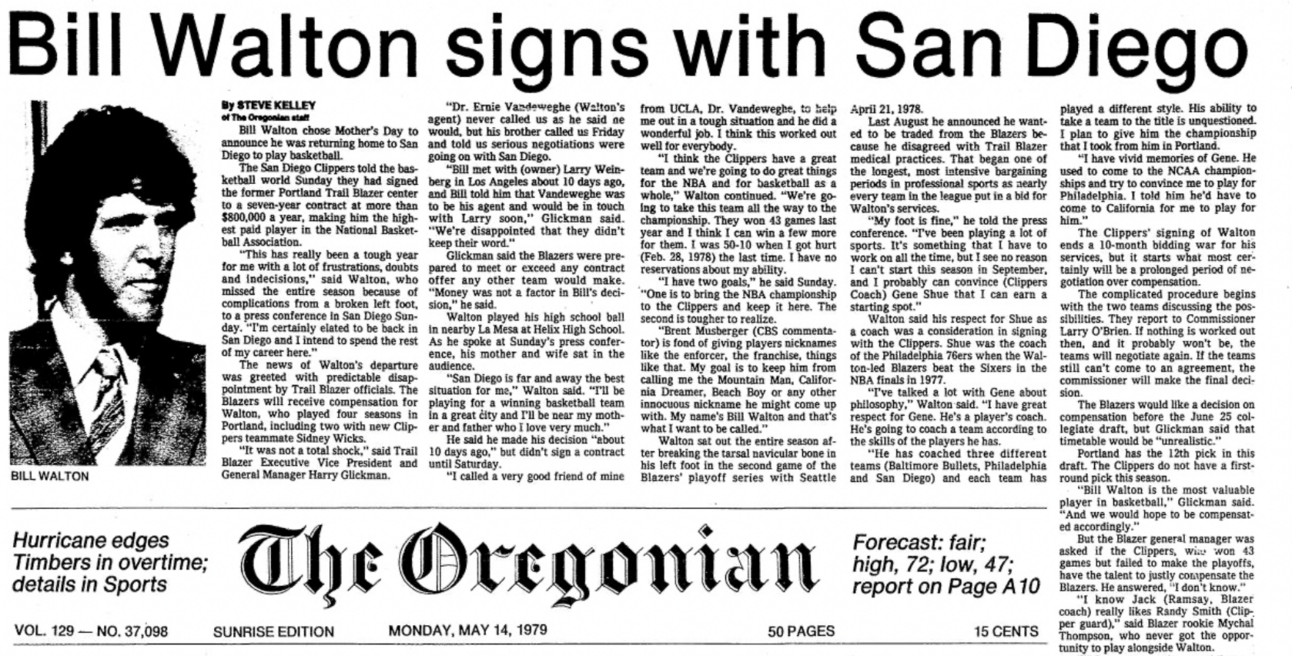

On Mother's Day, May 13, Walton agreed to a seven-year contract with the Clippers that made him the highest-paid player in the NBA at more than $800,000 per season, a big raise over his $450,000 annual salary in Portland. There was still the matter of compensation for commissioner Larry O'Brien to sort out. (At the time, league rules required teams signing a veteran free agent to send that player's old team players and picks.) Oregonian columnist Steve Kelley wrote that Portland should "ask for the players whose departure would most cripple the Clippers' future."

One of those players was forward Lloyd Free (later known as World B. Free), who told Kelley, "I'm not going to Portland." Free had played for Ramsay at Buffalo and said the two did not see eye-to-eye.

The compensation for the Blazers ultimately netted out to forward Kermit Washington, center Kevin Kunnert, two first-round picks and $350,000 in cash, which the National Basketball Players Association felt was excessive and appealed.

The Oregonian (May 14, 1979)

The appeal over compensation dragged out into the season, with The Oregonian reporting in November of 1979 that the commissioner was considering unilaterally sending Maurice Lucas to the Clippers to preempt a lawsuit from the players’ union. This obviously never happened.

Walton underwent ankle surgery that summer that kept him out until January and limited him to 14 games in the 1979-80 season. His third game as a Clipper was against the Blazers on Feb. 8, 1980, in San Diego, in which he had 13 points and 4 rebounds in 17 minutes in a 118-104 win.

Both The Oregonian and The Oregon Journal sent their beat writers to San Diego for the game, and both of their game stories, predictably, focused on Walton.

"Bill Walton missed the gusto, but settled for what's left," Wheeler wrote in the Journal. "Portland's Trail Blazers missed it, too, but they had nothing on which to fall back."

Walton didn't say much that day about his time in Portland or the circumstances behind his exit, only lamenting that most of his teammates were also gone.

The day of that game, the Blazers traded away two other core players of the 1977 championship team, sending Lucas and two first-round picks to the New Jersey Nets for Calvin Natt, and trading Lionel Hollins to Philadelphia for a future first-round pick.

The following day, Oregonian columnist Bob Robinson wrote a column titled "Trades Won't Fade Memories," reflecting on all three players' exits and wondering why Blazers players were continually unhappy with the team's management.

(The 1979-80 season from the Blazers’ perspective is the one David Halberstam chronicled in one of the all-time classic sports books, The Breaks of the Game, published in 1981.)

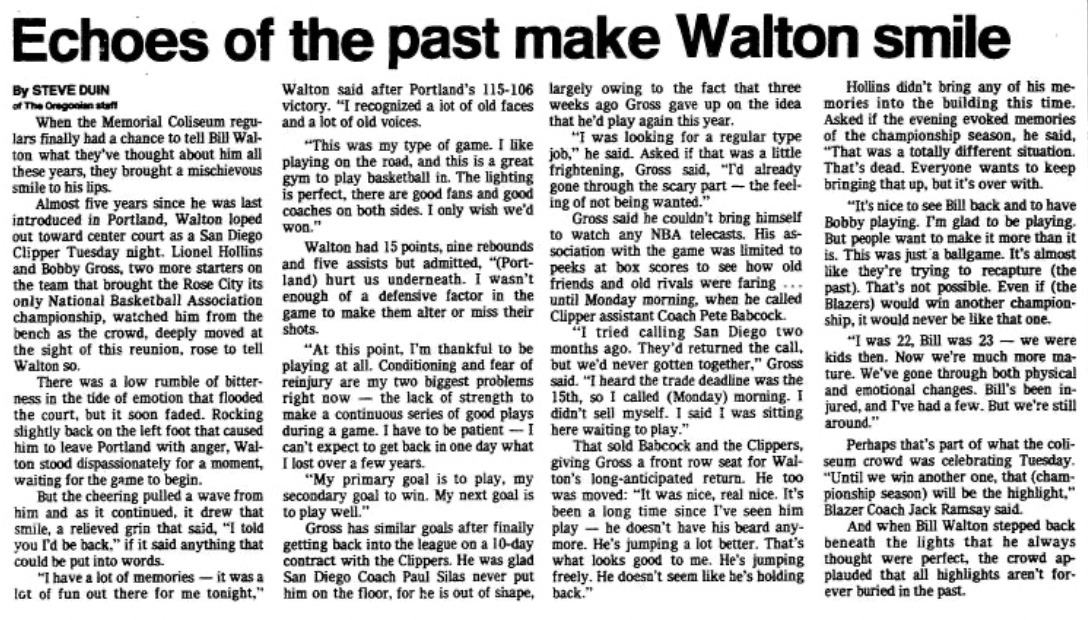

Walton missed the entire 1980-81 and 1981-82 seasons with foot injuries and didn't make his return to the Veterans Memorial Coliseum as a visiting player until Feb. 15, 1983. He had 15 points, nine rebounds and five assists for the Clippers, but the Blazers won 115-106.

By then, the Oregon Journal had been bought out by the owners of the Oregonian and merged into the bigger paper. Wheeler, the former Journal beat writer, was now covering the team for the Oregonian and handled the game story. Steve Duin, an Oregonian lifer who remains a columnist at the paper to this day, wrote a separate story focusing on Walton's feelings about Portland, which had softened considerably in the four years since the divorce.

"I have a lot of memories," Walton said. "It was a lot of fun out there for me tonight. I recognized a lot of old faces and a lot of old voices."

The Oregonian (February 16, 1983)