Will the Giannis Antetokounmpo Trade Talks Actually Involve the Trail Blazers?

Portland has been connected in multiple ways to the Bucks' superstar ahead of Thursday's trade deadline.

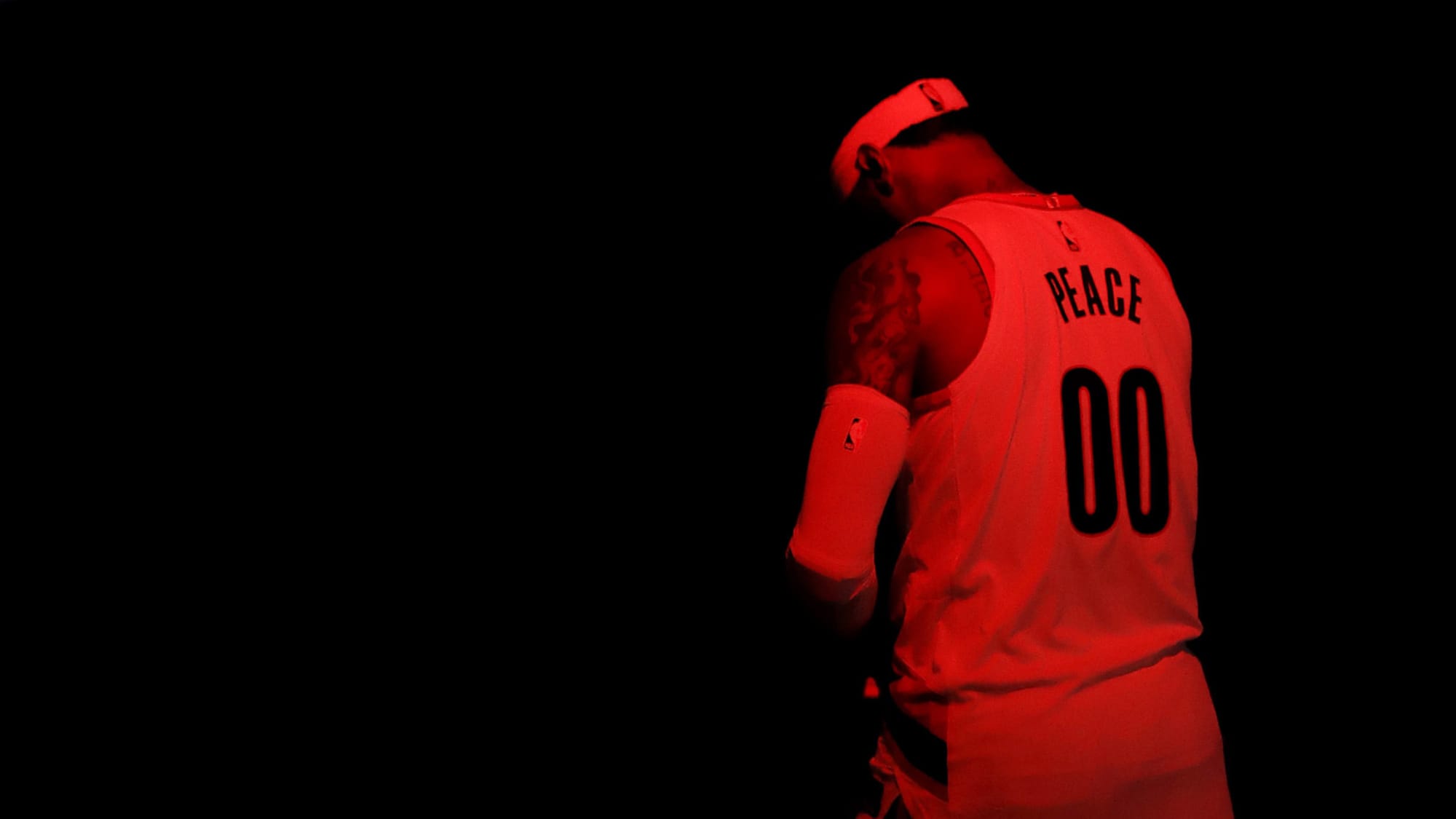

Anthony was out of the NBA for over a year before the Blazers gave him a dignified finale.

Inductees into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame don’t go in as a member of one team the way they do in baseball.

If they did, Carmelo Anthony’s plaque would undoubtedly feature a Knicks jersey when he’s officially enshrined this fall. New York is where he chose to go in his prime. It’s where he’s most loved, where he had his greatest individual success and where his No. 7 jersey will one day be retired.

Congratulations to 10x @NBAAllStar, 3x Olympic Gold Medalist, and member of the @NBA 75th Anniversary Team, #25HoopClass inductee Carmelo Anthony. pic.twitter.com/8kAZqGxs3o

— Basketball HOF (@Hoophall) April 5, 2025

Anthony would be a first-ballot Hall of Famer if his career ended after he left the Knicks in 2017. He didn’t need the brief time he spent with the Trail Blazers to cement that. He was only in Portland for two seasons, one of which was cut short by the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But I’ll bet he gives that chapter the appropriate amount of reverence in his induction speech, for what it meant for the way he ended his career.

In the beginning, it was a marriage of convenience, with Anthony and the Blazers solving each other’s problems.

Anthony had been out of the NBA for a full year following a disappointing season in Oklahoma City and a brief, disastrous stint in Houston. He needed a team, any team, to give him a shot at a better ending to one of the most decorated careers of the modern era.

And the Blazers needed him.

Coming off an unexpected Western Conference Finals run in 2019, Portland started the 2019-20 season 4-8 and had lost starting power forward Zach Collins to a season-ending shoulder injury. When he went out, their options at that position were either not NBA-caliber players (Mario Hezonja), well past their primes (Kent Bazemore and Anthony Tolliver) or not close to being ready for big minutes (rookie Nassir Little). Damian Lillard had just inked a four-year, $196 million extension coming off that deep postseason run, and it looked like another year of his prime would be wasted.

At that point, why not swing for the fences and see if Anthony had anything left?

“I had been trying to get Melo to Portland for a couple of years by that point,” Lillard told me earlier this season. “And then when he was out of the league and was struggling with it, I knew he was still working out. So when it was on the table, I said, ‘We need to get him.’ We needed more firepower.”

Something else Lillard said back in 2019, when Anthony’s arrival in Portland was still fresh: during the lead-up to the 2003 NBA Draft, when Anthony was coming off a national championship run with Syracuse and there was a legitimate debate between him and high-school phenom LeBron James, the then-13-year-old Lillard was a Melo guy.

Lillard didn’t just push for the Blazers to sign Anthony because he thought he’d be able to help the team—it was personal. The way one of his childhood heroes had been seemingly kicked to the curb by the NBA didn’t sit right with him. If Anthony was going to have a redemption arc, Lillard wanted to be a part of it.

“You’d think someone who’s had a Hall of Fame career would be able to go out with some respect,” Lillard told me at the time. “You don’t expect a team to be like, ‘OK, you’re off the team.’ It was weird.”

At the time, the league largely reacted with skepticism to the Blazers signing Anthony. His post-New York stops with the Thunder and Rockets had flamed out because refused to come off the bench or accept a lesser role. It felt like a repeat of the sad end to Allen Iverson’s career in Detroit and Memphis 10 years earlier, a once-great player unable to come to terms with his place in the modern game.

Would Anthony continue down that path in Portland, or would his extended time out of the league cause some self-reflection and allow him to commit to a Vince Carter-like late-career reinvention and change the perception around him?

The non-guaranteed one-year minimum contract he signed with the Blazers would suggest then-team president Neil Olshey wasn’t sure of the answer to that question when he brought him in.

Anthony joined the Blazers on Nov. 19 in New Orleans, in the middle of a six-game road trip. His first three games, losses to the Pelicans, Bucks and Cavs, were forgettable. But at the end of that trip, it changed. To close out the road trip, he scored 25 points on 10-of-20 shooting in a win in Chicago. Then, in his home debut at Moda Center, he had 19 on 9-of-11 shooting in a win over the Oklahoma City Thunder. He followed that up with 23 points, 11 rebounds and four assists in a win over the Bulls.

That week, the experiment went from being a possible trainwreck to a genuine feel-good story. Anthony’s brand-new No. 00 jersey (chosen because the Blazers haven’t given out his longtime No. 7 since Brandon Roy’s early retirement) sold out at the team store in the arena before his first game. Following those three breakout games, he won Western Conference Player of the Week for the first time in five years. Shortly after that, well ahead of the January deadline, the Blazers officially guaranteed his contract for the remainder of the season.

The way it was all working out was almost too good to be true.

His new teammates couldn’t believe it, either.

“I had a moment of, ‘This is really Melo,’” Jusuf Nurkić says. “He'd jab and pull up. I got spoiled playing with Dame and C.J., but having him around was special.”

Once the novelty of Anthony being back in the NBA wore off, both he and the Blazers settled into their new partnership. Anthony had some big performances but mostly deferred to Lillard. He was brought in to be a part of the team, and that’s what he was.

COVID shut down the NBA, along with the rest of the world, in March of 2020. When the season resumed in July in what is now known as “the Bubble,” the Blazers were one of the 22 teams invited to Walt Disney World but were outside looking in at the playoff race. They needed all eight of the regular-season games, and the inaugural play-in, to get in and set up a first-round series with the eventual champion Lakers.

Anthony had four 20-point games as the Blazers went 6-2 in those eight seeding games, and then a 21-point performance in a win over Memphis in the play-in game.

“When we went to the bubble and had to play all those games to make the playoffs, he came up big for us,” Anfernee Simons says. “He made some big shots.”

Anthony started all 58 games he played for the Blazers that season. But when he began talking to Olshey and head coach Terry Stotts about re-signing that offseason, it was made clear to him that if he came back, he’d be coming off the bench. The Blazers had just traded for Robert Covington, and Collins was healthy again.

Two years prior, Anthony had seemingly washed out of the NBA because he wasn’t willing to give up his starting spot. This time, he was ready to do it with no complaints.

“Seeing a Hall of Famer like that accept a [bench] role, as a young player, you've just got to roll with anything they throw at you,” Simons says. “If they want to change your role, you've got to adjust. If Melo will do it, I've got no excuse to complain about what my situation is.”

Anthony got some Sixth Man of the Year votes that year. The role suited him—at his age, he was still capable of big nights like the 29-point performance in a March 1 win over the Bulls, but he was no longer capable of doing every night what he’d done for years in New York. Having spent his first season in Portland proving he still belonged in the NBA, he leaned into being a glue guy and veteran mentor in his second year.

The younger players on that team still feel the impact. Simons jokes that he took for granted how clinically efficient Anthony was in the post and how little work he had to do as a second- and third-year guard learning how to throw entry passes. Nobody he’s thrown them to since then has been as effective. Few players in the modern NBA were.

“Having the chance to be around him and learn from him is one of the things I'm going to remember most about my career, for sure,” Simons says. “You always remember all the Hall of Famers you've been around. At the time, you don't really think about it until they're gone. But you see him now going into the Hall of Fame and it's crazy that I got to play with him.”

Right by the entrance to the Blazers’ locker room is a plaque with the names of all the winners of the Maurice Lucas Award. It's an honor the franchise created in 2011 following the death of the beloved member of the 1977 championship team, to recognize the player who “best represents the indomitable spirit of Maurice Lucas through his contributions on the court and in the community, as well as in support of his teammates and the organization.” Past winners include Lillard, Nurkić, LaMarcus Aldridge, Ed Davis, Jerami Grant and, most recently, Toumani Camara.

Anthony’s name is on that plaque, too. That Maurice Lucas Award, from his first season in Portland, is not a widely talked-about part of his legacy. Certainly not on the level of the stuff you’ll hear him bring up this fall in his Hall of Fame speech, the Olympic gold medals and All-Star and All-NBA appearances. But it’s an appropriate honor for Anthony's place in Blazers history.

This fanbase is one that remembers beloved role players forever—you’ll see just as many Wesley Matthews, Joel Przybilla and Nicolas Batum jerseys at any game at Moda Center as you will Lillard or Roy. Really, anybody not named Raymond Felton or Gary Payton II who has ever worn this uniform can lay claim to the mantle of “Blazers legend.” Hell, Drew Eubanks got a tribute video last season.

Unlike any of those guys, Anthony was famous. Real-world famous. The kind of famous where people who aren’t even basketball fans might know who he is. A level of fame even Lillard has never reached. In fact, Anthony is probably the most famous person ever to wear a Portland Trail Blazers uniform, except for maybe Scottie Pippen or Bill Walton. People like that don’t play for franchises like this.

That was not a small part of the novelty of it, locally. But once it was clear that Anthony didn’t just want some adoration or a farewell tour, that he was willing to embrace the phase of his career he was in on a team not built around him, the city was sold.

During Lillard’s time in Portland, the entire fanbase followed his cues, and the mutual admiration he and Anthony had for each other was obvious. Once he came back for a second year, it went beyond a novelty. Anthony had other offers that offseason after his make-good deal with the Blazers paid off, but he wanted to come back. That went a long way with fans.

Anthony’s final moment in a Blazers uniform was the 2021 first-round playoff series against the Denver Nuggets.

It was the end of an era in a lot of ways. Stotts was fired after Portland lost in six games to a Denver team missing most of its best players. It was the last time the Blazers were in the playoffs or were nationally relevant in any way. And it was effectively the end of Lillard’s run in Portland, even if he didn’t actually request a trade until two years later.

But the most enduring moment of that series came in Game 4, on Anthony’s 37th birthday. He had an OK game—12 points on 5-of-11 shooting in 21 minutes off the bench—and the Blazers won to even the series at 2-2. In the break between the third and fourth quarters, the Moda Center crowd sang “Happy Birthday” to him in unison.

This wasn’t too long after the Blazers started allowing a limited number of fans back into the arena. Most of Anthony’s second season with the Blazers was played in an empty building as COVID continued to rage. That spring, as the first vaccines began rolling out, the Blazers reopened their doors to a few thousand fans. By the playoffs, they were still selling only a little under half of the seats. (Remember social distancing?) The official attendance number for that game was 8,050.

But in that moment, it was as loud as any of the Blazers’ legendary playoff crowds in years past.

Anthony played one more season after that, checking off the last bucket-list item of his career by playing with James. Most people don’t remember that he even played for the 2021-22 Lakers and couldn’t tell you a single thing he did that year. He didn’t officially announce his retirement from basketball until a year later. By then, it was obvious he had nothing left to give.

Anthony became a superstar in Denver and played his best years in New York. But it was in Portland that he got to go out on his terms and write a dignified final chapter to his Hall of Fame career.